New Paths to DPI

We’re happy to report that Lobster Capital Fund I already has DPI after 2 years! This is extremely rare for a fund of our vintage (<10% of funds).

For venture fund LPs, DPI is the metric that rules them all.

When push comes to shove, DPI is the concrete thing that family offices care about. Unfortunately, among the most recent fund vintages, it’s also in increasingly short supply.

While other metrics like TVPI and IRR involve some level of projected financial performance, DPI measures only concrete results. Because venture firms often hold onto their investments for several years before finding an exit, it can also take several years for a venture fund to start generating significant DPI.

But this usual need for patience when it comes to DPI appears to be growing more extreme:

59% of 2017 vintage funds generated DPI after five years

Only 39% of 2019 vintage funds reached the same milestone

Half of all funds from 2018 vintage still haven’t distributed any capital after five years

This distribution drought comes at a particularly interesting time for family offices. According to J.P. Morgan’s 2024 Global Family Office Report, family offices now maintain a 45% allocation to alternative investments, with their tech venture allocation growing from 22% in 2021 to 30% in 2023.

Now they’re re-engaging with more sophisticated approaches and clearer expectations about returns.

There is a way forward, and it leverages family offices’ natural advantages of patient capital and strategic thinking. The answer lies in understanding where talent wars are creating unexpected liquidity events, and how focusing on systematically filtered ecosystems like Y Combinator can position family offices to capture these opportunities. At Lobster Capital, we’re seeing this play out in our conversations with our YC-focused portfolio, where talent-driven conversations are happening earlier and more often.

The Talent War Solution—Hot Deals Get Liquidity Faster

The AI talent wars are creating liquidity in unexpected places. These competitions for technical expertise are generating entirely new exit pathways that forward-thinking family offices should understand.

$100M Engineers

Silicon Valley has always overpaid for talent, but AI has pushed compensation into genuinely surreal territory. Companies are offering individual researchers packages that could fund entire startups, treating human capital like scarce artwork. The logic is simple: there are maybe 100 people on earth who truly understand how to build frontier AI models, and everyone wants to own them.

Even more eye-wateringly, it even makes sense! There is a great post here from Trace Cohen that breaks it down in more detail.

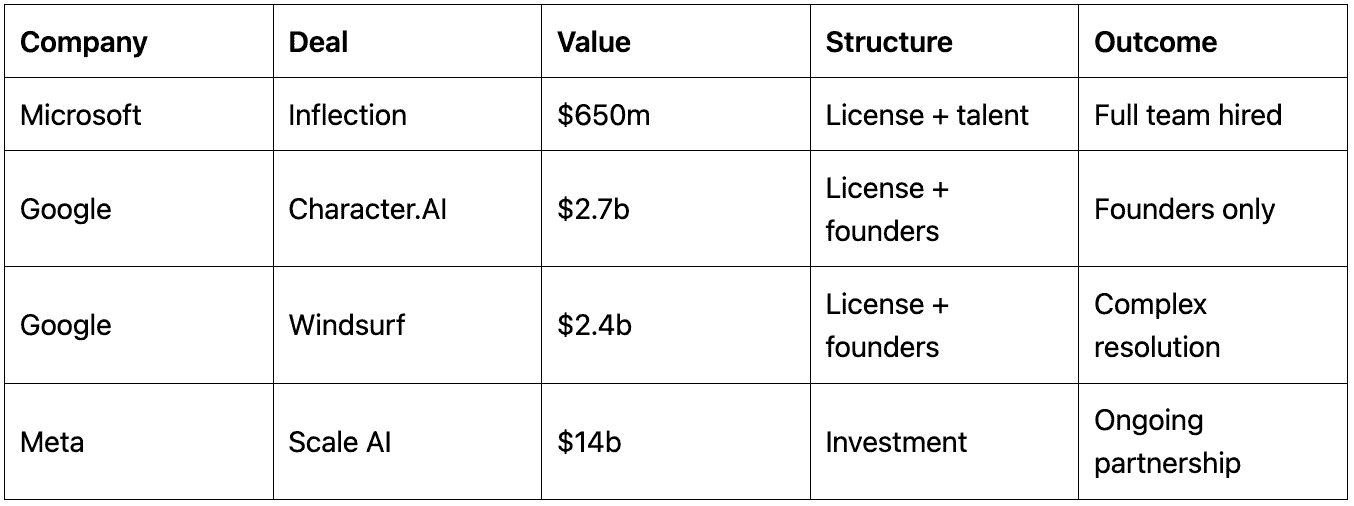

This frenzy has also extended to acquiring. Meta’s decision to ‘invest’ $14 billion in Scale AI and hire founder Alexandr Wang represents more than a partnership.

Zuckerberg was acquiring access to the team that built one of the most utilized AI data platforms, plus Scale’s ability to attract and develop talent that Meta couldn’t hire directly. This reflects a broader pattern.

Meta has been offering eye-watering $100-300 million packages over four years to individual AI researchers.

Google paid $2 billion for what amounted to acquiring Character AI’s Noam Shazeer and his team.

Amazon executed a reverse acquihire with robotics startup Covariant, bringing in the founders and 25% of the workforce.

These transactions are really talent acquisitions, structured as business deals. They happen at premium valuations with rapid timelines compared to traditional strategic acquisitions.

Why This Creates Earlier Liquidity

The talent shortage in AI and advanced technology is changing how and when companies get acquired. When AI jobs represent 5-6% of total software hires and specialists remain scarce, companies with the right teams become strategic assets regardless of their business metrics.

Companies acquiring talent evaluate different factors than traditional strategic buyers. They focus on team quality, technical capability, and cultural fit rather than revenue, market size, or customer acquisition metrics. This creates faster decision-making cycles with less regulatory scrutiny than traditional M&A.

The speed difference is substantial. Strategic acquisitions typically require 12-18 months of market development and due diligence. Talent acquisitions can complete in 3-6 months once the acquiring company identifies the team they want.

Acqui-activity surge: Big Tech increasingly using “reverse acquihires” to secure top AI talent—AI specialists now represent 5-6% of total software hires

Talent shortages driving premium valuations for teams with proven ability to execute

Speed advantage: Focus on team quality over business metrics creates faster exit cycles

YC’s Talent Filtering Advantage

Y Combinator’s value proposition to family offices extends beyond startup success rates. The accelerator systematically identifies the type of talent that Big Tech companies are actively seeking to acquire.

The Selection Mechanism

YC’s 2% acceptance rate creates pre-filtered talent pools. The accelerator’s selection process optimizes for qualities that make teams attractive acquisition targets: technical sophistication, ability to execute quickly, and founders who work effectively under pressure.

The numbers support this filtering approach:

Approximately 40% of YC startups ultimately achieve some form of exit.

45% of YC companies raise Series A rounds compared to 33% of seed-stage companies overall.

Median YC exit time reaches 4 years, with smaller exits (under $100M) completing in only 3 years.

Companies from 2014-2020 cohorts averaged 5 years to IPO versus 9 years for 2007-2013 batches.

The distribution is also interesting… about 90% of exits occur within 9 years, and these account for roughly 50% of exit dollars. Family offices focused on DPI rather than maximum IRR can build viable strategies around consistent, smaller returns rather than waiting for unicorn-scale outcomes.

The Acquihire Sweet Spot

Understanding what Big Tech actually acquires through talent transactions reveals a clear investment framework for family offices dealing with the DPI crisis.

What Big Tech Actually Buys

The highest-value acquihires share three characteristics.

First, technical teams with AI/ML expertise, which aligns with the skillset that YC companies develop through their technical founder focus.

Second, proven founder-market fit, meaning teams that have worked together and demonstrated ability to ship products.

Third, validated execution capability, shown by companies that survived YC’s process and gained early customer traction.

The Math That Works

The economics favor talent plays over traditional exit strategies. Acquihire valuations typically range from $1-5 million per engineer for top talent, with total transaction sizes often in the $10-50M range. Traditional exit valuations might be significantly higher but take 7-10 years to materialize, assuming they happen at all.

Risk-adjusted returns support the talent approach: a 3x return in 3 years compares favorably to a 10x return in 10 years, especially when the larger return carries execution risk, market risk, and timing risk.

Hunting the Talent Pipeline

Investment Thesis

Target YC companies with exceptional technical teams in AI, ML, developer tools

Focus on B2B companies: B2B companies exit more quickly and often than consumer

Bet on “acquihire insurance”: even if the business model fails, the team has value

Specific Sectors to Target

AI/ML infrastructure (following the Scale AI playbook)

Technical tools (clear value to Big Tech)

Robotics and automation (talent shortage in these areas)

Cybersecurity (always strategic value)

The Contrarian Bet

While other LPs wait for traditional exits, family offices can:

Get in early on talent-rich deals

Accept smaller but faster returns (2-4x in 3-5 years vs 10x in 8-10 years)

Build relationships with acquiring companies for future deal flow

Diversify across 20-30 “talent hedge” investments

Value Arbitrage

What’s actually happening is a complete reorganization of how value flows to the top of the economy.

For decades, the biggest companies accumulated value by buying market share, patents, and distribution channels. Now they’re accumulating it by buying people. The venture capital ecosystem has inadvertently become a vast talent-sorting mechanism for Big Tech—a kind of outsourced R&D department where the costs and risks of human capital development get socialized across thousands of LPs, while the successes get cherry-picked at premium prices.

Investors that recognize talent more as a scarce asset and position themselves in deals where talent wars create liquidity events will address their DPI challenges while others wait for traditional exits that may never materialize.